Advocates' Guide to Automated Notices

DownloadThis guide breaks down common issues with automated notices, what could be happening behind the scenes, and how to demand fixes. It maps what you might see on a notice to the potential causes, how parts of computer systems generally work together, and where fixes could be most effective.

- Introduction

Across states and public benefits programs, applicants and advocates have seen countless issues with automated notices. Common issues include omitting crucial information, including inaccurate or confusing information, or sending the notice to incorrect addresses. These errors create barriers to accessing benefits and may violate due process rights. This guide will help advocates understand how automated notices are generated in computer systems, common issues with automating notices, and potential strategies to address notice issues. As we will explain, automated notices typically have a mix of what we describe as static, conditional, and dynamic language, and may also include worker-inputted text. Issues therefore may occur because of how the basic static text was designed, how the system generates conditional and dynamic text, the actual text that is generated, or how a worker inputs information to the system or notice directly.

Changes to notices can, of course, address problems with notices themselves. Changes to notice language can also be used to try to reduce the harms of other, distinct issues with systems and processes. This guide will help advocates distinguish where issues originate and what fixes could be most effective in the short or long term. This knowledge can be very powerful in response to an agency or vendor that claims it cannot change its notices or is unable to identify underlying system errors that lead to issues in notices.

Quick terminology note: There is overlap between terms in the computer and benefits program context. In this guide, the “system” refers to the computer software, and the “program”—which is a computer term as well—refers to the benefits program, such as Medicaid.

- Notice Basics

When is notice provided?

The specifics of when a notice must be sent differ by benefit program. In general, notice must be provided any time an action is taken regarding a person’s eligibility for the program or their receipt of benefits. A notice usually must be sent in advance of the effective date of the action to allow a person to appeal and opt to continue their benefits pending the outcome of that appeal.

Why are notices sent?

The purpose of a notice is to inform a program enrollee or applicant of a decision affecting their eligibility for or receipt of services, provide them with the reason and basis of the decision, and provide the tools to appeal that decision. Adequate notice is an essential component of constitutional procedural due process and is also a statutory requirement for most public benefit programs. An individual in danger of losing or being denied a public benefit must be given an explanation of the reason for the impending loss or denial and a meaningful opportunity to challenge it via the appeal process.

What are the requirements that notices must meet?

The specific elements that a notice must contain are unique to each benefit program (see, for example, 42 C.F.R. § 431.210 for Medicaid and 7 C.F.R. § 273.13 for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program). In general, notices must clearly state the action the agency intends to take and the reason(s) why the agency is taking that action. Notices also must inform the individual of their right to a hearing to challenge the action.

With few exceptions, notices must be sent at least 10 days before the effective date of the action. Notices must also be written in language that is easy to understand. Advocates’ Guide to Automated Notices | 4Benefits Tech Advocacy Hub

For more information on specific Medicaid notice requirements, please reach out to the National Health Law Program, or NHeLP.

- Parts of an Automated Notice

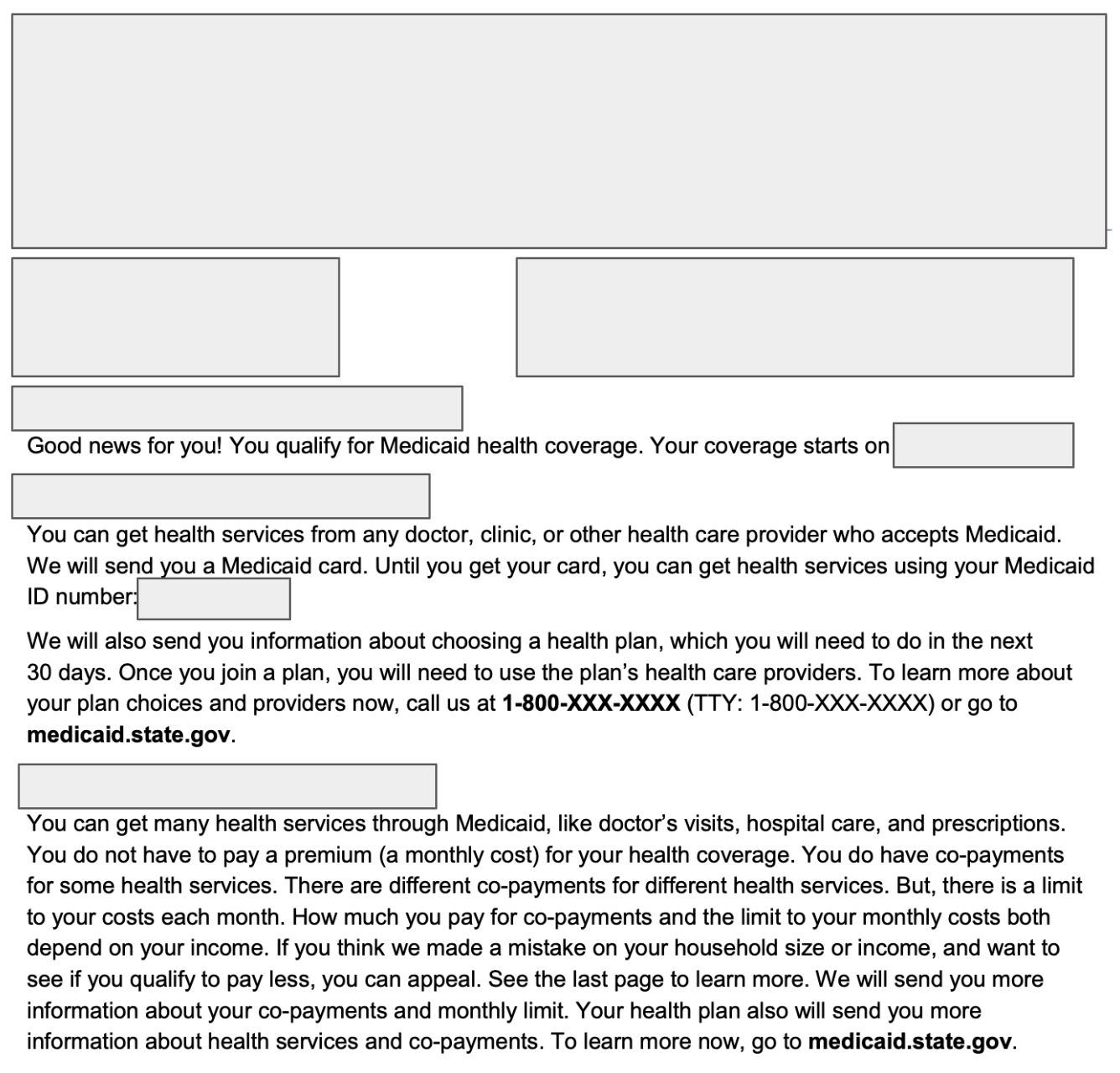

Below is a portion of an example notice from Medicaid.gov that we will break down into three types of text: static, conditional, and dynamic.

Although this notice is just an example, we use it to show which pieces of information on a notice are likely chosen for each individual during notice generation (conditional and dynamic) and which are standard (static) across all notices. It is useful to distinguish these three types of text because they can provide clues about what changes are needed to alter a program’s notices.

States may have notice templates available online that makes identifying these pieces easier, and advocates can also request notice templates through public records requests. The template will usually help you narrow down what pieces of text are dynamic even if there are not clear indicators of some of the sources of information that fill in the dynamic portions. There is a fuller explanation of templates later in this guide.

The three types of language highlighted here are:

1. “Static” language: This is the text that always appears on a notice and is not tailored to the individual. The following version of the notice shows only the static language:

2. “Conditional” language: This is the text that specifically describes the action being taken or why something happened. It is conditional because it changes depending on whether certain conditions are true, which relate to the circumstances of the notice. The following version of the notice shows only the conditional language:

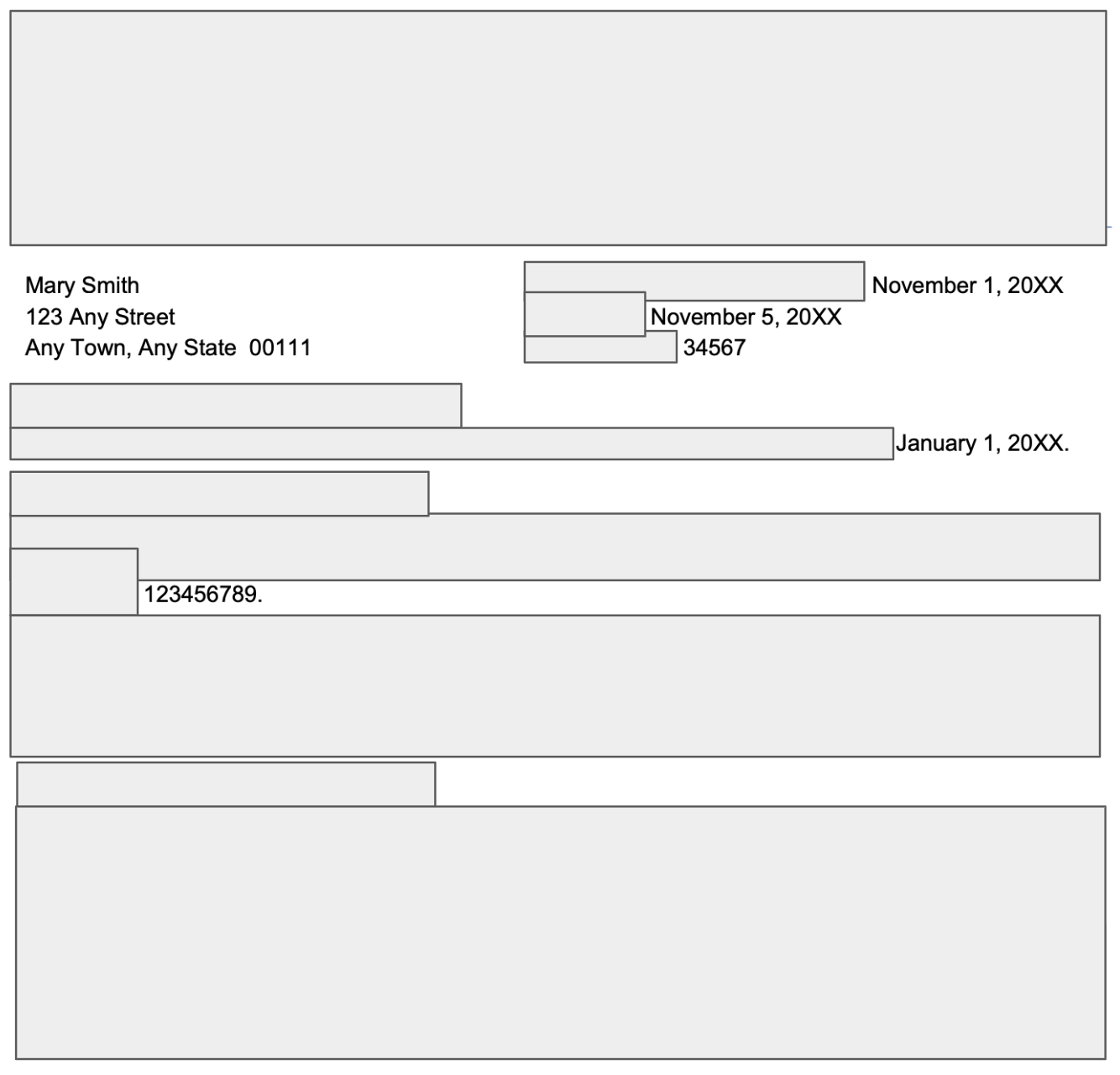

3. “Dynamic” language: This is the text that is case-specific information, including names, addresses, or income amounts. It is dynamic because it is the result of the computer inserting the data for that specific person into the notice. The following version of the notice shows only the dynamic language:

It is important to note that these are not terms of art—they are simply our descriptors of each kind of language included in notices. Recognizing these types of text will help you figure out where issues in a notice likely originate and what type of change is needed to adjust the problematic text.

Issues that come up in static language, for example, can be resolved by directly editing the language, just as is done in a Word document. The conditional language also can be directly edited, though some changes might also require changing the rules that dictate when the conditional language appears. And dynamic language can be added to a notice by inserting a placeholder for data to which the system has access.

Next, we will break down the general process for how this data gets filled in.

- How are Notices Generated?

Understanding how a notice is generated provides insight into where issues could be happening and what kinds of questions you can ask. Plus, it can help you request the appropriate modifications to notices to solve the identified problem.

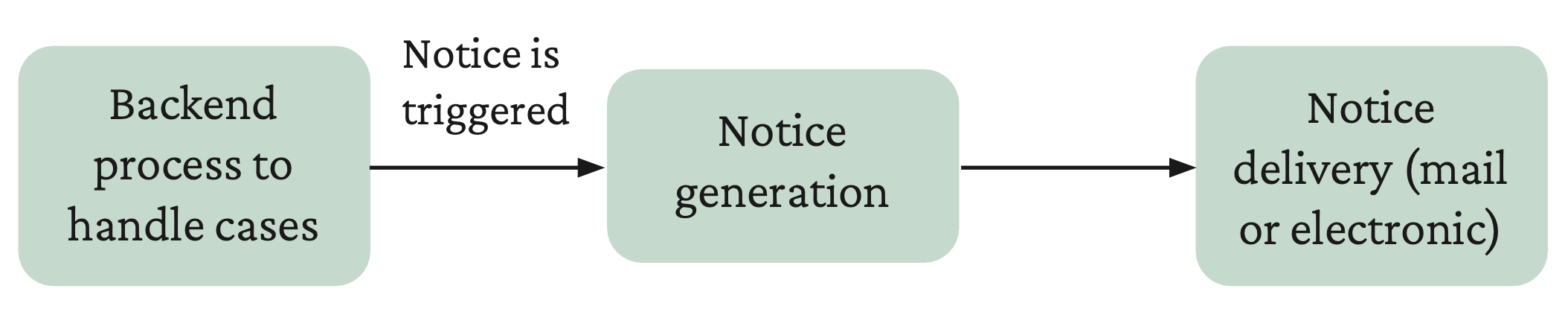

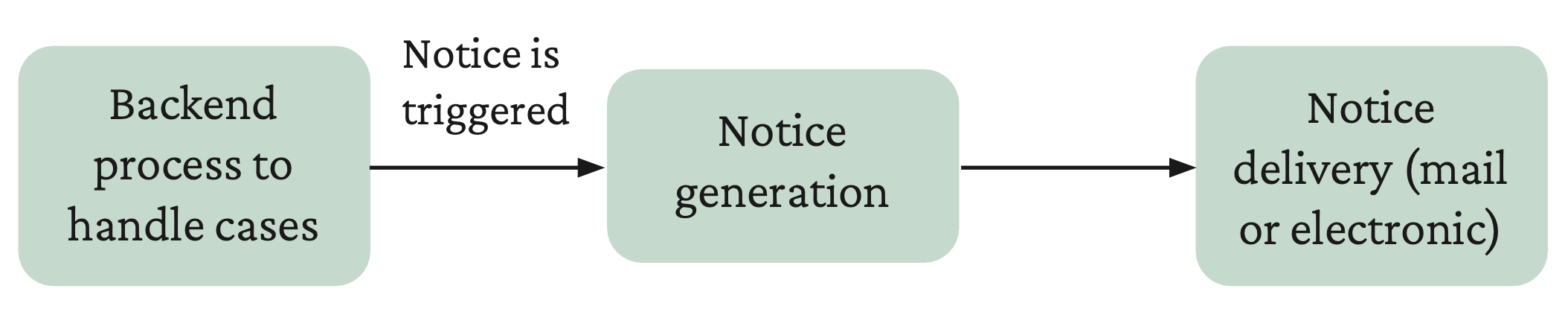

There are many ways to design a system that automates notices, but at a high level, there are usually three general stages to generating and sending a notice, all or some of which can be automated:

Backend processes to handle cases, during which the system keeps track of case details, makes eligibility and enrollment decisions, and flags when a notice is needed. This often involves:

- Adding the case details to a queue

- Processing all or some of the notice generation flags in the queue as a “batch” on a regular schedule (e.g., nightly or weekly)

Notice generation, when a template is selected for the situation and filled in with specifics (the dynamic and conditional language). This may involve:

- Fetching additional data from databases within the eligibility and enrollment system or from external databases (e.g., Social Security Administration database, State Wage Information Collection Agencies, or state unemployment databases)

Notice delivery, when the completed notice is sent to the mailing system or online portal.

We have split the process into three main phases because different people may be responsible for or capable of fixing issues that originate in each part. Someone without technical expertise, for example, can suggest static or conditional language for the template that could be a quick and effective solution to certain kinds of problems. It also shows how issues can appear in the notice but actually be due to an issue in the backend or communication processes. Similar to the types of language in notices, these are not terms of art or strict definitions but rather are the general phases of the process that we have seen.

These phases are not exact and may not be true for every system, especially if a system has more direct caseworker involvement. Some states, for example, have multiple systems where the components (case management system, notice generator) do not “talk” to each other and caseworkers thus need to transfer data between them manually. Other systems may be nearly completely automated. Even still, we think delineating these three processes is a helpful way to understand what happens behind the scenes to create a notice, so you can identify potential problems and see where interventions could happen.

- Mapping Common Issues to Potential Causes

Below is a list of common issues with notices and their potential origins, with clues to help reveal which source is most likely. While some of these issues can also be one-off errors (e.g., a typo in someone’s address), they are likely systemic issues if there is a pattern of the same issue across multiple notices or if the issues do not seem to be caused by something that a person would accidentally do. It is not likely, for example, that a person would choose to put a long, repetitive list of denial reasons on a notice, but a computer system might direct them to do so or might just do it automatically.

Incorrect personal information in the notice (e.g., address, income, name, deadline information)

These could be backend issues if:

- The notice shows old addresses or incorrect income for many different people, despite people having updated their addresses with the agency.

- You contact the agency and they have the same (incorrect) information that is on the notice.

- The notice contains names/data from people not associated with the case.

- There is a pattern of incorrectly calculated deadlines on the notices due to how the eligibility system is programmed (different from if notices are delayed and then deadlines are impossible to meet).

These could be notice-generation issues if:

- The agency has information in their files that is correct, and it is different from what is on the notice.

- The notice contains data from a different database than the one that the backend eligibility system uses.

Missing personal information in the notice

These could be backend issues if:

- The notice text has blank spaces or gaps where it seems information should be.

These could be notice-generation issues if:

- Other notices for different decisions have this information, but notices for this decision do not have it.

The basis for the decision is not provided, and instead overly simplistic explanations are shown (e.g., “You have been found ineligible because you do not meet eligibility requirements”)

These could be backend issues if:

- Notices have always been vague with the same boilerplate language on all notices, due to those details not being recorded on the backend or otherwise not being available for use in the notice.

- Notices used to have a lot of conflicting information on them and now they have none, which may be due to backend errors that were difficult to fix and then simply covered up. The eligibility decision may not be correct.

- Individual determination for each household member is not captured by the backend or accessible by the notice generator.

These could be notice-generation issues if:

- Some notices have more details while others do not, so it is likely that at least certain data from the backend gets to the notice generator.

- The eligibility decision is correct but does not provide information that was given in past notices, implying the information is accessible but now not being displayed.

- The agency has information on individual decisions, but they are not in the written notice.

Unnecessary or redundant notices are triggered (e.g., Requests for Information)

These could be backend issues if:

- This is most likely a backend issue with how the system manages cases or creates notice triggers.

People are not receiving notices or notices are very delayed, making for impossible deadlines

These could be backend issues if:

- These could be backend issues if: No one, or nobody from a certain group (e.g., eligibility category, people submitting appeals), is getting any notices. This could be an issue with how the system manages cases or creates notice triggers.

- If notices are going to old addresses, the system may not be updating people’s cases correctly with new addresses.

- The system does not account for the mailing timeline and expects responses infeasibly early.

These could be notice-delivery issues if:

- The postmark on the envelope or other delivery date information is significantly after the date on the notice. This can indicate a problem with mailing.

- Notices are only going to an online portal, but people do not know to check there. This could happen if a person opted in to electronic notices without realizing it or missed an opt-out notice.

Multiple conflicting or redundant reasons are listed for an individual’s or household’s eligibility or ineligibility

These could be backend issues if:

- Agency records reflect the same information that is on the notice, meaning there may be issues in how households are represented in the system or how eligibility rules are applied.

These could be notice-generation issues if:

- Most or all of the notices that the agency sends have a long list of potential (but not relevant) reasons, which could mean that there is overly broad or incorrect logic to decide which text appears.

Now that we have described some common issues and where they could originate, we will explain in more detail what happens at each of these phases (backend, notice generation, and notice delivery) more thoroughly. If you are trying to understand or troubleshoot a specific issue, you can jump straight to the section that is indicated for that issue in the table above.

Keep in mind, however, that some issues may be from worker input, as opposed to errors in the system design or operation. Worker issues can come up when the system does not give agency workers the right options for the situation or when workers have to manually complete pieces of the process, creating bottlenecks. These issues can mix with automation issues, but it should still be possible to determine the source of problems.

Backend processes

The backend refers to any system or software used to handle applications and cases. Usually, the main parts of the backend are the rules engine, the case database, and the batch processor. Problems with these components can affect whether rules are properly applied to cases, whether people’s cases are maintained correctly in the database, and whether notices are triggered at appropriate times.

Some issues that show up on notices actually originate in the backend. This means that what presents as a “notice issue” can mean that something is wrong with how decisions are being made or how casefiles are kept.

Rules engines

The rules engine is the part of the system backend that automates applying the eligibility rules to a case. The rules engine is essentially a flowchart (or “decision tree”) translated into code.

Yet the translation from eligibility rules, to decision tree, to computer logic must be done carefully and exactly, since the computer will only follow the literal code that is written. If any part of the rules is not translated perfectly, the computer may unintentionally apply different rules than what is expected. It is not uncommon for the nuances that workers understand from written policy to be lost in translation.

In the benefits context, programming errors could lead the system to take the wrong “branch” of the decision tree for the case and to apply rules that are not relevant to the case or individual—for example, using some income-based rules for a non-Modified Adjusted Gross Income case. Or it could be that the rules engine does not have the complete set of eligibility rules, so someone gets denied because their case does not fit the eligibility categories that the system does have.

Reason codes are any labels or flags used to capture details about someone’s eligibility and pass them along through the system. In some systems, caseworkers select a reason code from a preset list, while in others, the system picks the reason code as it is applying the eligibility rules in the rules engine. In the latter case, it looks like the rules engine checking if certain conditions are true, and if they are, then assigning the reason code that corresponds to those conditions.

Different systems have different approaches to reason codes. Some only keep track of one reason code at a time, with the assumption that there is one primary factor leading to the decision. Others keep track of all reason codes that are encountered while applying the rules, with the assumption that multiple reasons might be relevant to the case or to individuals within the case.

The rules engine transforms eligibility decisions into reason codes and flags, which are used to determine notice language within the notice-generation process. This means that when the conditional language on the notice is incorrect, it actually could be reflecting an incorrect underlying eligibility decision or an incorrectly assigned reason code.

- Inappropriate conditional language that traces back to the rules engine could have various causes:

- The system applied the wrong rules due to misprogramming and selected that associated reason code.

- The system, while following the decision tree, applied the wrong rules before applying the right rules but did not dismiss the wrong rule’s reason code. This can happen if the rules engine is programmed to look at all potential rules independently, instead of exiting the tree once eligibility or ineligibility has been determined.

- The system applied the right rules but was misprogrammed to select the wrong reason code.

- The system applied the rules to multiple individuals within a household but applied the (potentially conflicting) reason codes to the entire household.

- The system might not be designed to record specific reason codes or flags at all (for example, only saying an individual or a household was approved or denied).

It is also the case that the rules engine may be functioning correctly, but the notice generator could take those correct results and mishandle them while generating the notice (which will be discussed in the “Notice Generation” section below).

Another crucial aspect of rules engines is the creation of a “hierarchy” of rules—as in, the order in which the rules are checked matters, especially when it comes to how reason codes are assigned. Rules engines usually have a “nested” design, where conditions are checked within each other. In Medicaid, for example, the rules engine may first check if the applicant requires an income determination by the agency or if their coverage is based on enrollment in other programs (e.g., Supplemental Security Income), and then, only if they aren’t in those programs, it does an income check.

An overly broad first branch, however, could pass through cases that are not meant to have the ensuing rules applied. Then, depending on whether the rules engine is written correctly, the case may or may not eventually end up in the branch where the relevant rules apply, but, in the process of being evaluated for the wrong rules, it may have captured irrelevant reason codes that make it through to the notice and trigger irrelevant conditional language to appear.

Unlike human caseworkers who have expertise in the written policy, the rules engine cannot “look around” for the right rules to apply—it simply follows the instructions with which it is programmed. This means that exemptions and eligibility categories may be completely passed over, leading to incorrect denials and notices that do not give helpful information. This is especially likely if the system is not properly designed to handle mixed-eligibility households, for which different individuals are subject to different eligibility requirements.

Strategies to fix these issues may depend on the design of the rules engine. It could be faster, for example, to add a place within the template for human caseworkers to add context than it would be to add in new reason codes to a system that does not already have them—though relying on caseworker input can lead to less consistency in the notices. Determining whether there seems to be an issue with the rules engine can help you ask for a more tailored workaround to catch the cases it seems to be affecting.

Cases database

Each state program has a way of storing cases in their computer system. The important aspects of the case database are how cases are represented as data, how they are organized, and what systems or people have access to them.

A “case” can be modeled as data in different ways. Regardless of the exact model, the system needs a way to correctly associate individuals, households, personal information (e.g., addresses, income, etc.), and eligibility decisions. This requires careful design because eligibility rules are nuanced and enrollee information changes over time.

It is also important that cases are organized so that information can be accessed or changed—for example, when someone needs to be added to or removed from a household. If the wrong case is accessed or if the case’s associated household cannot be modified, then the wrong eligibility decisions may be made.

Further, the relevant systems and people need to be able to access the case database. Many case databases do not “talk” to other systems with which they should interact, such as online application systems or rules engines. This means that information may be passed around manually by caseworkers, leading to long wait times for case processing and the potential for human error.

If there are issues with the databases, they might show up in a notice as personal information that is incorrect (e.g., regarding someone outside the household or income data that is not right) or out of date (e.g., old address that had been on file). Specifically, the dynamic parts of the notice are often pulled from a database or case management system if they are not entered into the notice directly by a caseworker. Errors with the dynamic parts of the notice could be from a one-off worker mistake when managing a particular case (e.g., entering the wrong address or income data) or could be from a systemwide problem with the database (e.g., the database is offline or casefile-data changes do not propagate to all places that contain copies of that data).

Issues with any of these elements can be structural and require technical expertise to address but also can be less disruptive if caseworkers are aware of them.

Batch processors

Not every system uses a batch processor, but it is a popular system design concept. It simply means that the system creates a running list of action items throughout a day (or other amount of time) and then processes them all in a sequence at the end of the day (or time period). This running list of action items is the batch and, for the purpose of notice generation, is the list of cases that need notices generated for them.

In other words, it is as though a person spent the day drafting letters and then went to the printer in the evening and printed them all out at once, instead of drafting a single letter, printing it out, and then starting the next letter, and so on.

Issues with batch processing can show up when the time intervals between processing actions is very long (so notices do not get generated in a reasonable amount of time) or when action items do not get correctly added or removed from the queue (resulting in duplicate notices or no notices). There may be a programming issue, for example, with how the system determines which cases require a request for information, such that these cases end up in the batch repeatedly, triggering an unnecessary request for information notice each time.

Backend process questions

- Does the rules engine have all the eligibility rules?

- Does the rules engine process all categories automatically, or does it send certain categories to caseworkers? If so, when and what are the triggers?

- What happens if the system does not choose the correct set of eligibility rules to apply? How does the system alert eligibility workers or users of errors? What kind of monitoring or testing is there for errors?

- When, if ever, is there human intervention in the process? Are any eligibility categories completely automated? What role does the eligibility worker play when the category is not automated? How does the system identify cases that cannot be automated? What happens in those cases?

- What are the components of the state’s eligibility system? How do workers interface with each component? What training manuals or design documents show these processes?

- Where does the system get the data to make eligibility determinations? Where in the system does eligibility data live? How does this data get updated once the eligibility determination is made?

- How frequently is data pulled from data sources? Are all possible sources updated at the same time?

- How is data being pulled in from other sources (e.g., based on name, based on a unique identifier)?

- Does the state/agency accept self-attestation as opposed to documentation for any categories?

- When data sources contain information that is incorrect or out of date, how is the correct information fed back into these sources to ensure the conflict does not repeat in the future? What other steps are taken to prevent the same problem in the future?

- What testing is done to ensure that the logic is working correctly on an ongoing basis, that human intervention is flagged appropriately, and that human intervention is accurate?

Notice generation

Once the system identifies that a notice needs to be generated, a different part of the system or a separate system handles creating the notice. Generally, notices are generated from a template. The system may have separate templates for each type of notice (e.g., an eligibility determination, a request for information, etc.) or it might have one long template with conditional language for each possible context.

The notice-generation process involves a mix of data sources, boilerplate language, and potentially caseworker involvement. This means there are a lot of moving parts and potential for error.

Templates

Issues with templates can be more straightforward to identify and fix than other parts of the process. This is because the templates are made up of a lot of regular text, similar to a Word document, along with some basic computer code. Yet there could also be issues with the system that fills out the template, including whether it has access to the right databases to fetch data.

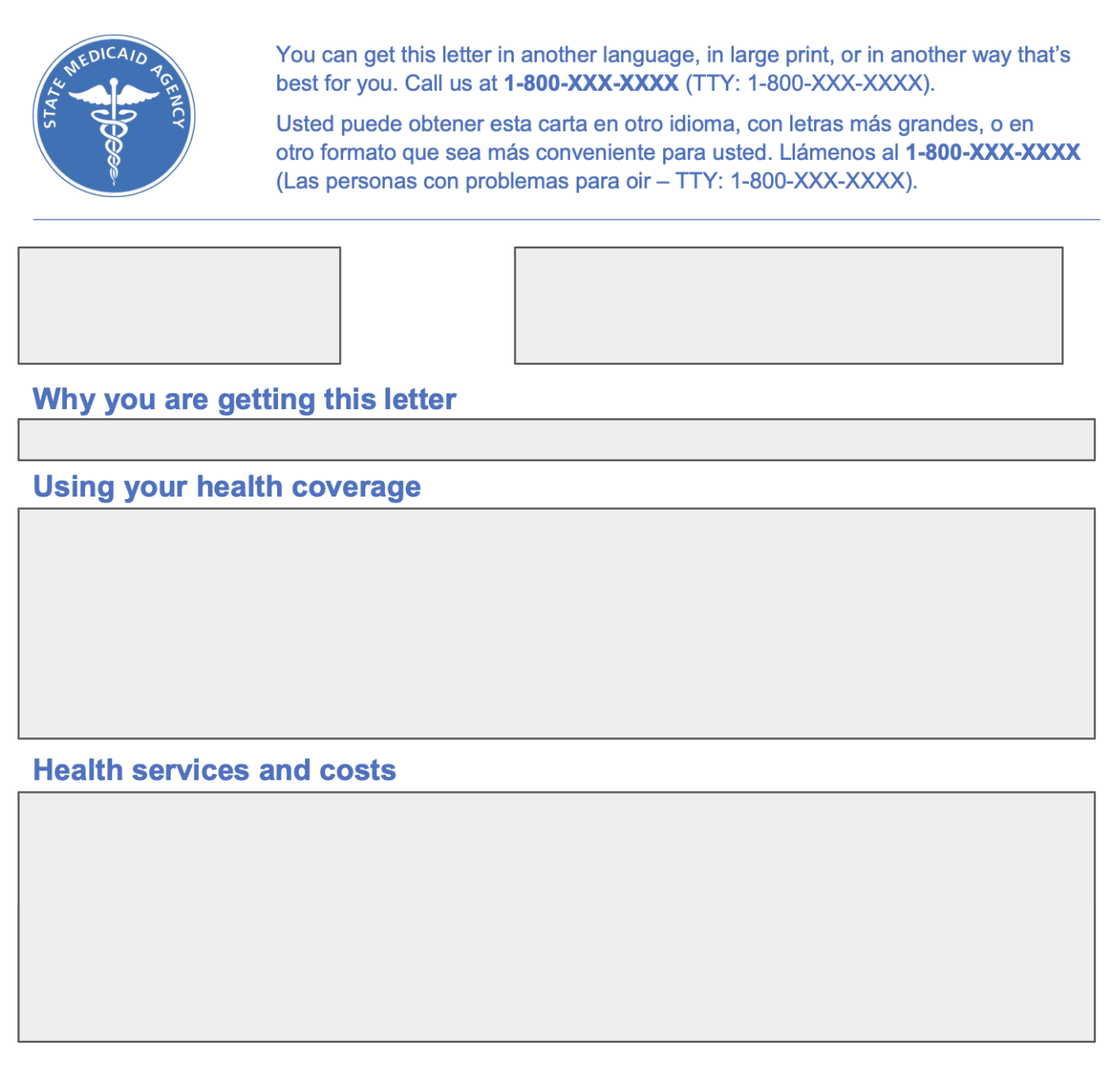

Templates are made up of static, conditional, and dynamic components that correspond to the notice output language, similar to what was seen in the Medicaid example earlier. Static language appears the same in the template and in the notice, but conditional and dynamic language that appear on the notice are represented differently in the template.

A template for the Medicaid notice example above may look something like this (though note that notices describing income determinations should include additional detail, such as the calculations used to reach the eligibility decision):

[APPLICANT NAME] Health coverage application date: [APP DATE]

[APPLICANT NAME] Health coverage application date: [APP DATE][STREET ADDRESS] Letter date: [LETTER DATE]

[CITY], [STATE], [ZIP CODE] Letter number: [LETTER NUMBER]

Why you are getting this letter

If (application = approved):

Good news for you! You qualify for Medicaid health coverage. Your coverage starts on [COVERAGE START DATE].

If (application = denied AND reason_code = 555):

We reviewed your application. We decided that you do not qualify for Medicaid health coverage. To learn more, read the “How we made our Medicaid decision” section below.

You might still be able to get health coverage—and help paying for it—through the Health Insurance Marketplace (Marketplace). We sent your information to them. The Marketplace will send you a letter. To learn more, read the “Complete your Marketplace application” section below.

If (application = denied AND reason_code = 777):

We got your application from the Health Insurance Marketplace (Marketplace). They did not think you qualified for Medicaid, but you asked for our review. We reviewed your application. We decided that you do not qualify for Medicaid health coverage. To learn more, read the “How we made our Medicaid decision” section below. You still qualify for health coverage—and help paying for it—through the Marketplace. Be sure to read the letter they sent you. You can also call them at 1-800-318-2596 (TTY: 1-855- 889-4325) or go to HealthCare.gov to learn more.

How we made our Medicaid decision

If (application = approved):

We counted your household size and income based on what you told us on your application and information we got from other data sources. We found that your household size is [HOUSEHOLD SIZE] person and your income is $[MONTHLY INCOME] each month. Since your monthly income is below the Medicaid income limit, you qualify. Because you qualify for Medicaid, you will get coverage without needing to buy health insurance. This means you do not get help paying for health insurance through the Health Insurance Marketplace. Medicaid offers many services at low or no cost to you.

If (application = denied AND reason_code = 555):

We counted your household size and income based on what you told us on your application and information we got from other data sources. We found that your household size is [HOUSEHOLD SIZE] person and your income is $[MONTHLY INCOME] each month. The Medicaid income limit for your household size is $[LIMIT(HOUSEHOLD SIZE)] each month. Since your monthly income is above the limit, you do not qualify for Medicaid health coverage. If you think we made a mistake, you can appeal. To learn more, read the “If you think we made a mistake” section in this letter. We made our decisions based on these rules: 42 CFR 435.119, 435.603.

If (application = denied AND reason_code = 777):

We counted your household size and income based on what you told us on your application and information we got from other data sources. We found that your household size is [HOUSEHOLD SIZE] person and your income is $[MONTHLY INCOME] each month. The Medicaid income limit for your household size is $[LIMIT(HOUSEHOLD SIZE)] each month. Since your monthly income is above the limit, you do not qualify for Medicaid health coverage. If you think we made a mistake, you can appeal. To learn more, read the “If you think we made a mistake” section in this letter. We made our decisions based on these rules: 42 CFR 435.119, 435.603.

This example shows how the template uses conditional “logic statements” (those in bold and italic) to describe the situation that corresponds with the conditional text (in indented paragraphs) to make them show up on the notice. These logic statements are computer code and can refer to facts about the case, such as whether it was approved or denied and the reason why. The variables (“application” and “reason_code”) containing facts about the case may be set by caseworkers (e.g., by selecting from a drop-down menu), but if the system is mostly automated, they are likely set in the backend by the rules engine.

It is important that the logic statements are written precisely because the computer will only add the corresponding text if the statement is entirely true (see how there is an “AND” in many of the statements). It is also important that the text in the template matches with the situation described by the logic—as in, the template uses reason code 777 (an arbitrary example number) to mean the same thing that it means in the backend rules engine.

This example also shows how dynamic text (seen in [BOLD UPPERCASE IN BRACKETS]) actually starts as a placeholder in the template and gets filled in for each notice. The words in the brackets refer to specific pieces of data to which the notice generator is assumed to have access. A caseworker may also be able to manually type in the information suggested by the placeholder, such as address or household size.

Templates can include varying amounts of static, conditional, and dynamic components. In this example, there are three conditions that this template can handle: approval, denial for income, and denial for income after an initial review by the agency.

Some systems use a comprehensive template for all notices and handle the different situations through a long list of conditional logic statements. Others use a different template for different buckets of actions, such as approval, denials, or requests for information. Still other systems may contain separate templates for every situation, so there is only static language and dynamic placeholders, with the conditional logic used to select a template.

Some notices are fully automated, but many are triggered by some action by a caseworker. To generate a notice, the system or caseworker pulls up the appropriate template (containing the static language) and then evaluates the conditional language elements for which text to add. Then, the system pulls in the data for the dynamic placeholders.

Or it may look like a table, where a caseworker or the system selects a row from a table similar to the one below.

Reason code Conditional language 000 (Approved) Your application for Medicaid has been approved. 555 Your application for Medicaid has been denied due to income disqualification. Your income is [APPLICANT_INCOME] for a family of [HOUSEHOLD_SIZE], which is over the limit of 138 percent of the federal poverty limit. 777 We did a second review of your application. Your application for Medicaid has been denied due to income disqualification. Your income is [APPLICANT_INCOME] for a family of [HOUSEHOLD_SIZE], which is over the limit of 138 percent of the federal poverty limit. Conditional language, including rules engines from the previous section, can have programming or design errors. If the system only has one slot for a reason code for ineligibility, for example, relevant information for the applicant may be left out. On the other hand, if there are multiple applicable reason codes or pieces of conditional language, they may contain conflicting information but still all make it into the notice. In both instances, the person receiving the notice often has not been given a clear statement of the reasons supporting the intended action.

Similarly, dynamic placeholders are programmed to pull up data, such as a person’s address. If that data is incorrect or missing, the notice may show the wrong address or a blank space.

Data sources

The data that goes into the template must come from somewhere. Most of it likely comes from the backend case management system, but the notice generation process may also involve other databases held by the state, or even third-party databases. Data from the primary case management system is the “master” record, so it should reflect updates to cases, but secondary or third-party databases might not have the same updates.

If you can figure out the databases from which data is coming (by directly asking the state or by looking at design documents of the system), it may reveal that the notice generator is fetching out-of-date secondary data and causing confusion. It may also reveal that the notice generator is simply pulling the (incorrect) data from the primary case database, which reveals further-upstream issues in the backend.

Changing which data the template fetches is very feasible if it is already able to fetch from the desired database (e.g., it may fetch address information from the primary database but fetch income data from a secondary database even though the primary database also contains income data). Where database connections do not exist already, however, new connections may need to be built. Workers can also be instructed to manually reference a different database to get the correct information into the notice.

Notice-generation questions

- How does the notice generator access information that is stored in the case database? Does it fetch data from other databases? Which ones? Does the case management system also have access to those other databases?

- How are notices generated? Are notice templates used for specific scenarios?

- Is there just one notice template, or are there multiple? Do the templates have specific text added to them for specific situations? What are the notice fields and options? (Note: you can request that the agency share their library of notice templates with you either through a direct ask or through a public records request.)

- How was the notice text developed?

- How is it translated into information for the applicant when information in their application “violates” the system’s eligibility rules?

- Does a human review notices for accuracy and clarity before they are sent? If not, how does the state/agency guarantee that notices are clear and accurate?

- When are notices sent? Does the state/agency ever send multiple notices? If so, what kinds of situations garner multiple notices?

- Is there any periodic review of the state/agency’s notice processes to ensure clarity, consistency, and accuracy? (see, e.g., Colorado audit below)

Notice delivery

After the notice is created, it must be sent out to the addressee. It is either physically mailed or posted to an online portal.

When it is printed and mailed, the computerized processes connect with physical processes. This can lead to issues because the computer is programmed to assume things about its available resources, which may not be correct. The system might assume, for example, that a notice can reach its recipient by mail within 5 days, when in reality, the postal carrier may pick up mail once a week. Or the computer might assume it can print a notice 10 pages long, but that might require a physically larger envelope that the agency or its mail processor does not have. Or there may be other delays in the state’s process for getting the notices from electronic format to printed format to actually send out for mail processing.

When it is posted to an online portal, the computerized processes have to deal with human behavior. Issues can happen when the agency or the computer expects that people will use the portal in certain ways, but these assumptions can be inaccurate. The agency may wrongly assume, for example, that a person knows about the portal, can access it, knows that they should check it for a notice, and knows how to log in. It may not send the notice by mail if it has been posted to the portal. Additionally, the methods used to alert a person to a notice for their review are important. Does a person receive a vague email, for example, stating “an important notice is in your account” for all manner of letters, including the ones that people tend to ignore?

Practically, these issues can require careful observation to pin down because it is about how pieces of the overarching system work together in practice. You can look for trends between printed dates and when notices arrive. You can also try (through public records requests or in litigation discovery) to get design documents or worker training manuals from the agency, which could have information about its processes and assumptions.

Issues with the mailing or portal system can be countered with a realistic assessment of agency resources and with testing of notice delivery assumptions (e.g., collecting data on how many people can log in to their accounts and open the notice). If the agency can only mail out envelopes weekly, that should be accounted for in the notice dates and deadlines. Similarly, if people are not checking the online portal, the agency should invite feedback to determine where the bottlenecks are and test alternative access methods.

Fixes to the notice-delivery process might actually need to be made in the backend or in the template. A template could be modified, for example, to have a different date appear, or deadline extensions could be programmed into the backend.

Notice-delivery questions

Online portal:

- What kind of performance monitoring and testing do you do of your online portal?

- Has the online portal experienced outages?

- Is there a backup plan in place/built-in redundancy to ensure that applicants and enrollees still receive communications in a timely manner even if the portal is experiencing an outage?

- Does the state/agency send notifications by other methods (phone, text, or email) when there are new communications in the online portal? Are people able to select their preferred contact method, including adding contact information for other enrollees/applicants?

- Does the state/agency record when enrollees/applicants open/view communications in the portal? If online communications are not opened/viewed, is there a plan to ensure the notice/information gets to the applicant/enrollee?

Accessibility:

- How does the state/agency ensure that all forms, notices, and websites are accessible? Do websites conform to accessibility guidelines? Are forms and notices provided in an appropriate font, size, and contrast?

- When is the state/agency verifying accessibility for online and digital materials, including screen reader compatibility? What about physical materials?

- What assistance is available in the event that an enrollee/applicant experiences accessibility issues? How do you ensure that affected individuals understand how to access that assistance and that they are able to make complaints about accessibility if needed?

- How does the state/agency fulfill accessibility-related requests? For individuals who make accessibility-related requests, are their requests noted as permanent or otherwise tracked and provided on an ongoing basis?

Language access:

- What languages are the state/agency’s forms, online portals, websites, other digital materials, notices, and other communications available in?

- How does the state/agency inform people that they can request materials in languages other than English?

- Are all translations completed by qualified translators and verified for context clues and reading level?

- Are automated processes programmed to automatically populate forms and notices in an individual’s preferred language? Are there prompts for human review to ensure materials are in the correct language?

- Does an eligibility worker pick the relevant language, or does the system choose the language to populate the fields? If it is done by a system, what are the choices, and what is the logic used to make those choices?

- Are individualized forms and notices only translated once finished? How are they flagged as needing translation?

- If the state/agency uses chatbots, will they be able to respond and communicate in different languages, as well as read around common errors in spelling and grammar?

- Does the state/agency rely on automated translation services that are not reviewed by human translators? How do they check/correct for errors?

Mailing and address issues:

- Does the state/agency mail notices far enough in advance to give the recipient a meaningful opportunity to act before a deadline? Does the timing of notice production and mailing take into account delays that can be expected due to limits on agency resources or changes to USPS delivery standards?

- How does the system handle returned mail? If mail is returned, does the system attempt to retrieve updated address information from other data sources before contacting the enrollee?

- Does the agency monitor success rates of reaching applicants and enrollees who do not have permanent addresses? How does the agency ensure that it reaches this population?

- Rectifying Notice Issues and Challenges

A faulty system does not excuse violating due process rights. When notices do not fulfill legal requirements, advocates can work to protect individuals through changes to the system. Some system changes may happen more quickly than others. Advocates may therefore want to pursue changes that can help prevent harm to individuals while longer-term systems changes are made. Understanding how the notices work, which pieces are more readily changeable, and which things may be affected by worker training can all help identify what specific changes are needed.

Workarounds

One interim way to prevent harmful notices is to get the agency to set up workarounds for caseworkers. Even when notices are automated, there are still usually places within systems where a caseworker may be able to intervene in the process. There may be opportunities, for example, at the point before a notice is mailed out for a caseworker to review it and either rectify language or remove duplicates.

For workarounds to be reliable, they should be integrated into the process, documented, and paired with administrative letters or other policy alerts. Adding flags to screens in the computer system, for example, lessens the likelihood that a caseworker will forget to check for a known issue. Documentation and policy alerts can inform caseworkers of systemic issues to watch out for proactively, such as for improperly determined eligibility categories.

Further, advocates can ask that the state informs them of known errors with notices so that they can better support clients proactively. A state could have a website, for example, that lists identified problems, for both notices and the system generally, so that both case workers and people impacted could identify that they may have been impacted by a system issue and need to have a human review their case.

Fixing the system

When it comes to fixing the system itself, it can be hard for states or advocates—who may not have access to the technical details of the system—to determine exactly what kinds of fixes are needed and how to implement them. This is made worse because states often rely on information provided by contractors about the amount of time and resources a fix requires, without independent verification of those estimates. The timing of fixes also may be complicated by vendors having regularly scheduled times during which they apply updates to their system to not disrupt service. Regardless, it should be possible to implement fixes sooner, or to at least build in workarounds.

Advocates can counter narratives from vendors about fixes taking inordinate amounts of time by using the questions earlier in this guide and by asking for different kinds of changes. It would be very technically simple, for example, to add new text options in a system where caseworkers pick language from a drop-down menu or table. It may also be possible to add explanatory language to the screens the workers use to make choices so that they better understand when to use different options.

Some backend issues can be mitigated within the template by changing the text that corresponds to information obtained from the backend. When implementing this type of change, though, you would need to clearly understand the logic that leads to those individual language choices to ensure it remains accurate for all related scenarios.

While some fixes are genuinely technically complicated, vendors may use vague technical terms that imply any change to the software will be a huge effort when this is often not accurate. Estimating feasibility matters for deciding whether advocates should also push for interim workarounds—and regardless of complexity, advocates should push for things to be done right.

Adding a new reason code, for example, could entail modifying and retesting the rules engine code and then adding new conditional language to the template. This does require some technical effort but remains doable within a relatively short timeline because most of the infrastructure already exists. A more complicated scenario would be if two systems were built totally separately and required a new process to send data between them—a situation where workarounds and public documentation could help meet people’s needs while the vendor is building and testing the new component.

Neither of these, however, is at the scale of recreating the entire system from scratch, despite what timelines given by vendors can sometimes imply. Regardless, the state has an obligation to provide adequate notice, and neither statements about the complexity of changes nor the state’s promise to make changes will alleviate states of their legal obligations.

- Proactive Accountability Measures

States should have procedures in place that ensure notices are adequate before they get to recipients. This includes inviting feedback during the design stage, testing notice generation processes fully before launch, and performing ongoing monitoring of notice delivery, usefulness, and accuracy.

Notice quality control: An example from Colorado

In 2017, in recognition of the importance of “accurate, understandable, timely, informative, and clear correspondence” from the state to Medicaid applicants and enrollees, Colorado passed the Medicaid Correspondence Improvement Process Act, Section 25.5-4-212, C.R.S. The law codified a specific definition of “correspondence” and implemented specific requirements that all Medicaid correspondence issued after January 1, 2018 must meet.

That same year, Colorado also passed another law, Section 25.5-4-213, C.R.S., requiring that the state conduct audits of Medicaid applicant and enrollee correspondence in calendar years 2020 and 2023. The 2020 audit found at least one problem in 67 of the 100 notices sampled and made two broad recommendations for systematic improvements to Colorado’s Medicaid correspondence scheme. The 2023 audit found at least one problem in 90 percent of the letters that were reviewed, including duplicate, contradictory, and confusing messages, inconsistent dates, and missing information, among other issues. The 2023 audit also found many of the 2020 audit issues remained because recommended changes had not been fully implemented.

Similar accountability measures could be important in other states to monitor system performance, including whether individual communication and communications received over a period of time by an individual are clear, understandable, and meet legal requirements. While Colorado looked at the information provided by the notice, it did not closely examine whether the notices reflected accurate decisions, which is also important to monitor. This would include monitoring of each step of a determination process, such as whether requests for information are understandable and sent appropriately or if denial notices are accurate.

Federal Office of the Inspector General reports about Medicaid eligibility determinations in California, Massachusetts, and Ohio indicate that such evaluations—especially if they include larger sample sizes, sample sizes by eligibility categories, and a deeper evaluation of why there were errors—would be useful to identify system issues.

Vendor roadblocks

States generally hire a private vendor to build all or part of their eligibility and service determinations system, which includes notice generation. States work with vendors to draft notice templates, reason codes, language, and processes, with the vendors largely building the infrastructure for creating and filling in the templates.

Depending on the state’s contract with the vendor, the state may have to pay for the system changes to match to regulatory changes, meaning regulations may not even take effect in practice without additional payment. While additional payment is not unusual because it is additional work, a state may find itself limited in what it wants to do regarding a rule change versus what it wants to spend to make those changes. Advocacy to states regarding notice changes have sometimes been stymied by vendor responses about labor and time costs to make those changes. Nevertheless, none of these issues can absolve states from their legal responsibility for ensuring their notices comply with due process. With a better understanding of the notices system, advocates may be able to help identify simpler, and often cheaper, solutions to fix the notices than what the vendor is proposing.

As with any procurement process, states should weigh the benefits and risks of vendors in the field, what they want out of a system, and the qualities and capabilities they desire of a vendor, as well as any contractual terms regarding fixing a system or penalties for dysfunction. Careful procurement and contracting language, for example, would better enable a state to push the costs of system improvements back to the contractor if the system does not meet the original specifications in terms of performance or functionality, particularly if a vendor promises its own expertise as a backstop to ensuring a system meets the state’s obligations.

States may also consider what monitoring procedures should be included in the design, as well as minimum transparency requirements so that the basics of the rules engine and logic is available for public review, as are any monitoring reports. Transparency paired with advocacy helps prevent issues before they impact people, such as when Missouri published plans to update their Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services eligibility algorithm and advocates pushed for changes.

Further, states can look for vendors that allow the agency to directly change their notices, especially for static and conditional text. A state may also consider other qualities in vendor selection, such as the mission of the organization, or if it is a nonprofit or B-corp organization.

- Conclusion

Understanding the components of automated notices can be very useful to advocates in identifying and potentially fixing notice and systems issues. Advocates can make proposals to the state agency about what to fix and can push back on potential state claims that changes are too costly or impossible.

Even with improved notices, there should be ongoing monitoring of communications, including notices, coming from automated eligibility systems so that errors are noted as soon as possible and corrected with both intermediate and long-term fixes, as needed. Importantly, known issues that appear in notices and other communications should be public so that relevant parties can understand if they are affected and how to address the issue.

Automated notices can help get benefits to people faster than manual processes, but the burdens of technical failures must not fall on applicants or enrollees. And technical complexity is not an excuse for states failing to meet their legal obligations.

[APPLICANT NAME] Health coverage application date: [APP DATE]

[APPLICANT NAME] Health coverage application date: [APP DATE]